How schools fail disadvantaged children

Philip Nye

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Study concludes some schools 'manage out' poorer pupils to boost exam league table results, with dire consequences for attainment.

School moves are a part of the education system that receive relatively little attention.

In Who's left, a study published earlier this month, we found that leaver rates from secondary schools in England vary enormously - in some cases, the number of pupils who left at some point between Year 7 and Year 11 was as much as half the number who finished their education at a particular school.

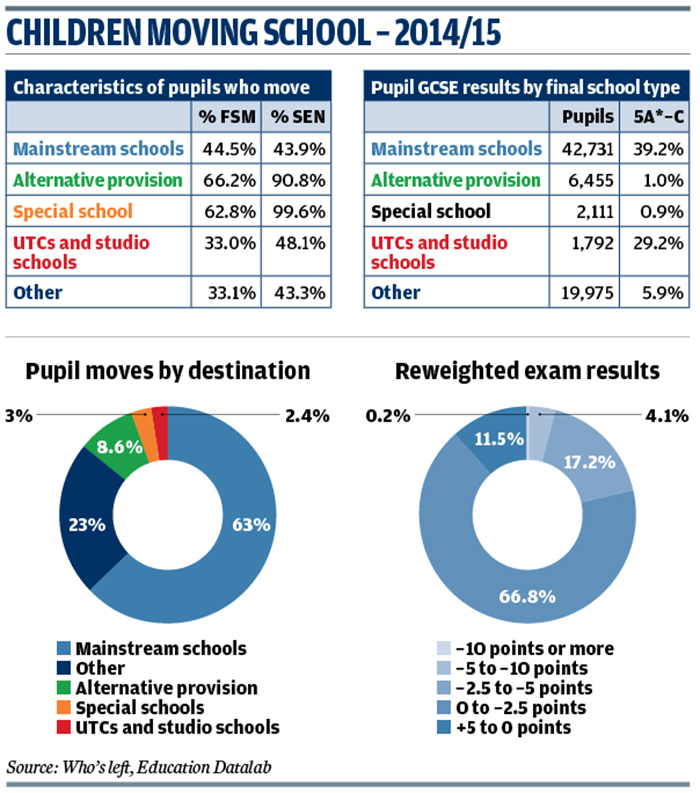

Those who move were more likely to be eligible for free school meals (FSM), and to have special educational needs (SEN), than those who stayed at a school.

Of those who move to alternative provision, two-thirds had been eligible for FSM at some point during their secondary education, while nine out of 10 received SEN support (see table).

We also identified a group of nearly 20,000 pupils who rarely feature in discussion about the education system, but who we think need greater attention.

This group left the rolls of mainstream schools, but did not join the roll of another state school or state alternative provision again before they reached the end of Year 11. They went on to a mixture of places: we think most went to independent alternative provision, independent special schools, further education colleges and private schools, while a minority will have left England altogether, or in a small number of cases, passed away. Of this group, a third were eligible for FSM, and more than two in five were receiving support for SEN.

We found that children who moved schools also had worse outcomes than those who didn't. Even for those who moved to a mainstream school, only 39 per cent achieved five good GCSEs including English and maths, compared to a national pass rate of 57 per cent for all children in mainstream schools (see table).

Of those we looked at who moved to state alternative provision, only one per cent achieved five good GCSEs, while in the previously unidentified group of 20,000 pupils who move out of state education entirely, only around six per cent achieved five good GCSEs.

League tables

We also looked at the impact on schools' league table results of pupils leaving their rolls. League tables are incredibly high-stakes for schools now, with results both affecting their ability to attract pupils and also determining whether they are in line to receive special attention from the Department for Education and Ofsted.

We found the league table impact of pupils leaving their rolls was very significant for some schools - with GCSE pass rates up to 16 or 17 percentage points higher than they might otherwise be as a result in some cases.

We worked this out by reweighting league tables, so that schools were accountable for all children who had spent time with them, in proportion to the amount of time they had spent there - in contrast to how league tables work currently, which are based mainly around who is left on the roll of a school in Year 11 (see graphic).

There have long been tales of schools encouraging parents to remove difficult children - sometimes with the suggestion that a permanent exclusion on a child's record is in nobody's interest. These are sometimes referred to in slightly euphemistic terms: managing out; grey exclusions; or off-rolling.

Our concern is that, in a small number of cases, some unscrupulous schools might be using pupil moves to "game" the league tables and boost their apparent performance.

It is worth saying that having large numbers of pupils who leave in itself does not mean that a school is using pupil moves to boost their results. Parts of the country with large numbers of immigrant children are likely to see more pupils move in general, and in some places, there are more alternatives to mainstream education to which a child could move.

But there have been persistent claims that some schools use pupil moves to boost results, and the findings of our work add to our concerns about this.

Given the poor outcomes of those who leave mainstream schools, and the fact that disadvantaged children and those with SEN seem to be overrepresented in this group, this only increases the need to look at this issue.

So our challenge to the DfE is to ask whether it is satisfied that pupil moves are always taking place in the best interests of both the child and the school - and that results are not being "gamed" by a minority.

The DfE is already considering making mainstream schools accountable for the outcomes of pupils who move to alternative provision or are excluded.

We are asking them to go further, and consider whether league tables should be reweighted so that all pupils count in league tables in proportion to the amount of time they spent at a school.

By Philip Nye, researcher, Education Datalab.

Education Datalab is an independent research organisation www.educationdatalab.org.uk

Expert view: Anne Longfield, children's commissioner for England

It is vital that we are ambitious for all children and do not give up on those who do less well or who may be challenging, and this means including those who are often ignored or marginalised.

Over the next few years, a key priority for me is identifying children who are otherwise ‘invisible' - this could be because they are either hidden within official statistics or missing entirely. I believe these are children who may be vulnerable but whose needs are not identified or recognised in policy and I want to focus on their outcomes.

The Education Datalab research identifies a cohort of children who (in a few schools) may be getting systematically excluded so that their results don't contribute towards the schools' published results. Effectively, these children are being hidden from view.

My concern is for the outcomes of these children. A child hidden is a child who can be ignored and I am concerned that there may be children being given-up on because schools think they reflect badly on them. The research suggests that the outcomes for this group - those removed from mainstream schools - are extremely poor.

We should not give up on any child. A child in Britain will spend 13 years in full-time education costing the best part of £100,000. No child should leave school with nothing, and even where a child is struggling to get five A*-C GCSEs (the national benchmark) schools should still be supporting that child to achieve whatever they can.

In recent years, there have been moves away from focusing on children obtaining five good GCSEs and towards a more inclusive and comprehensive system of measuring pupil progress, so it is troubling if schools are excluding pupils who may not be reaching this benchmark.