Links between SEND and offending

Professor Hannah Smithson and Professor Katherine Runswick-Cole

Tuesday, November 22, 2016

High numbers of children with SEND enter the youth justice system because of inadequate support.

The overall number of children and young people entering the youth justice system has fallen year on year since 2009.

There are currently 20,544 young people entering the youth justice system in England and Wales for the first time, while the number of under-18s in youth custody (870) is at an all-time low.

While these should be recognised as positive trends, there remain stark contrasts among different groups that have contact with the youth justice system.

The disproportionately high number of children from black and minority ethnic heritage in youth custody has been highlighted by campaigners, but young people with a special educational need and disability (SEND) are also disproportionately represented.

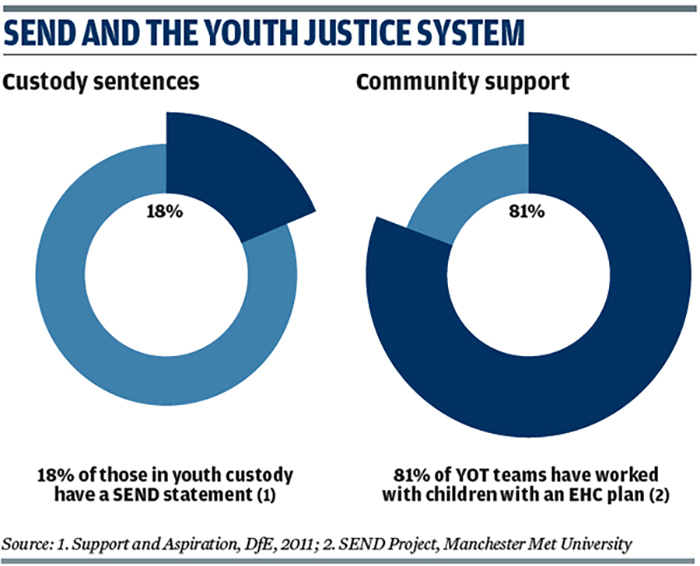

Young people with a SEND are five times more likely to enter the criminal justice system, with 18 per cent of sentenced young people in custody having a statement of special educational needs, according to a 2011 Department for Education study (see graphics).

These statistics suggest a strong link between ‘having a SEND' and becoming ‘an offender'.

The recent publication of a House of Commons justice committee report - The Treatment of Young Adults in the Criminal Justice System - recognises that neuro-developmental disorders such as a learning disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autistic spectrum disorders are particularly prevalent in the young adult prison population.

Our research - developed with the education charity Achievement for All and the Association of Youth Offending Team Managers - about existing provision for young people with SEND, is generating some interesting initial findings. A survey completed so far by a third of all youth offending teams (YOTs) in England shows four out of five respondents stated they had worked with young people with education, health and care (EHC) plans in the past year.

EHC plans are used to outline the needs of a young person with SEND and the services they should receive to address these.

In addition, our emerging findings show that of those young people with an EHC plan, the most prevalent conditions are ADHD; speech, language and communication difficulties; moderate learning difficulties; and autism spectrum disorders.

Responding to the challenge

Broadly, there seem to be two types of responses. The first is to individualise the problem by focusing on what it is about this group of children and young people that leads to offending.

This response focuses on the type of condition children have been diagnosed with, and asks what it is about these that leads to offending? This approach focuses on how we can screen children and deliver tailored interventions that will divert individuals off the path of youth offending.

But this response makes a fundamental mistake by relying on the assumption that there is an inevitable link between the nature of the individual child's SEND and offending. There is not.

Many children and young people with SEND grow up without ever being in contact with the criminal justice system, and, when they do, they are much more likely to be the victims, rather than the perpetrators, of crime.

The second, more helpful, response is to think about the systems and structures in which children and young people become "a problem". When a child with speech and language difficulties becomes disengaged from education, this is not a result of their condition - it is the result of system failure.

While the introduction of EHC plans offers the promise of joined-up services for some children and young people with SEND, many who end up in the criminal justice system will not meet the thresholds for being allocated an EHC plan.

They may not even be identified as having SEND until they enter the criminal justice system.

Possible solutions

Meeting this challenge is huge. Teachers are part of the system that includes professionals from health, social care, youth offending teams, speech and language therapists, magistrates, parents, and children and young people.

Bringing together a team around the child for all children who need it is increasingly challenging in a time of cuts to children's services.

Yet, focusing on challenging the limitations of the system, rather than the "failings" of the child, might present new opportunities to change.

These could open up opportunities to holistic approaches of working. Our current Department for Education-funded research will see Achievement for All develop an online community space - called the Bubble - for workforce training and development addressing the specific context of SEND reform implementation in the youth justice system.

The Bubble supports dynamic, daily communication, for example, to rapidly gauge opinion and shape creative thinking, stimulate innovation and consult on emerging recommendations.

Above all, it will be a common platform, language, and set of expectations and articulate a consistent approach for practitioners to reflect on, learn from and develop their professional practice.

- Hannah Smithson is a professor of criminology and youth justice; and Katherine Runswick-Cole is a professor of critical disability studies at Manchester Metropolitan University