More work is required to achieve 26-week care proceedings target

Neil Puffett

Monday, April 13, 2015

As Ministry of Justice figures reveal that 44 per cent of family court cases are missing the 26-week duration limit, experts look at this complex issue and assess what can be done to reduce unnecessary system delays.

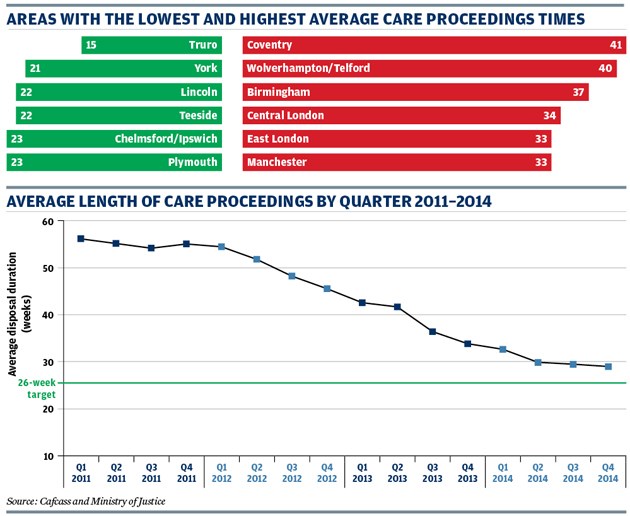

According to statistics compiled by the Ministry of Justice, the average length of cases completed between October and December 2014 was 28.7 weeks.

A breakdown of the figures shows that while 56 per cent were completed within 26 weeks, the remaining 44 per cent ran over.

Plans to introduce a 26-week limit were first announced by government in February 2012 after the move was recommended in the Family Justice Review carried out by David Norgrove, former chair of the Family Justice Board.

Although the limit was not a legal requirement for cases initiated prior to 22 April last year, a number of other steps were taken to cut down on unnecessary delays while the legislation was passed.

This has resulted in significant progress in recent years (see graph).

In early 2011, the average duration of care proceedings stood at more than 56 weeks. By the end of 2012 it had dropped to about 45 weeks, and by the end of 2013 it had fallen further to 33.6 weeks.

However, the fact that the average for October to December 2014 - the first quarterly reporting period for which cases initiated since 22 April 2014 were due for completion - remains above 26 weeks, indicates there is still more work to be done.

Indeed, statistics provided by the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) show that 28 out of the 42 regional family court areas in England (67 per cent) missed the target.

So why is the target not being met, and what needs to be done to ensure it is?

While it is true that some older cases that had been running for a long time are likely to have come to an end during the final quarter of 2014 - thus distorting the averages - this is not likely to have had a major impact on the statistics.

Anthony Douglas, chief executive of Cafcass, says that although the average length of cases continues to be on a downward trajectory, some areas are finding it far harder than others to hit the timescale, for a number of reasons (see table).

"Some areas have had long-standing cultures (of timely court proceedings) and have been top performers for many years," he says. "Others move around a bit (in terms of performance) because of short-term spikes in, or changes in, demand.

"Then there are the areas such as London and Birmingham that are trickier in the long term because they have high volumes of work and staffing issues, meaning it is more difficult to bring average case durations down to the standard of the best."

Judges' discretion

Douglas adds that some delays are caused by "positive developments" in the system - such as the expansion of programmes like the family drug and alcohol courts, which aim to keep families together but can result in cases taking more than 26 weeks to complete.

Indeed, judges do have the discretion to extend time limits in "exceptional circumstances".

"Sometimes cases are longer than 26 weeks for good reason - not just delay," Douglas says.

"The New Orleans intervention model (currently being trialled in Glasgow by the NSPCC) can take anything up to nine months, but if that addresses the underlying issues it is justifiable.

"If you take the small number of legacy cases and take extensions out of the equation we are averaging under the 26-week limit, but clearly some areas are not there yet."

Going forward, Douglas says it could be useful for government to publish more extensive information, breaking down how many cases have been extended, the reasons for extensions, and average times of court proceedings for cases that have not been extended.

"It would be a good area to have a look at," Douglas says.

Maud Davis, co-chair of the executive committee of the Association of Lawyers for Children, says it is currently unclear how many extensions judges are granting.

"There's no standard approach (to extensions) by judges," she says.

"It's very much about looking at the situation that presents itself on the day and the judge deciding what's necessary and how exceptional the circumstances are.

"Invariably they are complicated cases with a lot of children involved.

"I'm aware that cases in the family division of the High Court are tending to take longer, because they are more complicated cases sometimes with an international element.

"I believe judges have taken (the 26-week limit) extremely seriously and have pushed people where they think they can be pushed, but accepted cogent arguments for an extension."

However, Davis is concerned that certain issues could hamper the ongoing drive to reduce delays in care proceedings.

She says many local authorities have previously covered the difference in expense between the cost of using experts in some cases and the amount they receive in legal aid to cover it.

"Going forward, fewer local authorities will be able to pay the difference between the legal aid rate for experts and the rate the experts actually charge," she says.

"They just don't have the resources to pick up the difference. The worst case scenario is that you end up arguing in court about where the money should come from."

She also highlights the issue around retention of social workers.

Latest figures from the Department for Education show that, as of 30 September 2014, there were 4,320 vacant full-time children's social worker posts across English councils. This compares with 3,610 in 2013, an increase of 19.7 per cent. During 2014, 17 per cent of children's social workers left their job, compared with 15 per cent in 2013.

"There is a particular problem about retention and the number of changes of social worker during proceedings," she says.

"Professor Eileen Munro's report needs to be implemented in relation to standards for social workers and ongoing training, and creating conditions to keep good social workers. There is no sign of that happening at all."

Ann Haigh, chair of Nagalro, the professional association for children's guardians, family court advisers and independent social workers, says there are always going to be cases that require more than 26 weeks.

"In some cases it may be necessary to extend it in order to get a really good viable analysis of family members coming forward.

"They don't always come forward right at the beginning of the process.

"Sometimes it takes families a while to realise how seriously matters have progressed, or they may not even have been aware the case was before the court right at the beginning.

"Nobody wants delay and we should all be seeking to avoid it, but there may be particular reasons why that isn't possible."

Great progress

Andy Elvin, chief executive of fostering and adoption charity Tact, says great progress has been made to get the average case length down to less than 30 weeks.

"As long as it doesn't creep back over 30, I don't think the fact that it isn't under 26 weeks is the end of the world," he says.

Indeed, his concern is that too much haste could lead to important things being missed by social workers.

"We have noticed in adoption cases that there seems to be more cases where issues with children, particularly health issues such as foetal alcohol syndrome, Asperger's or autism, which could be argued to be foreseeable, were not flagged up before the adoption," he says.

"There is a worry about whether that is due to practice not being good enough, or whether it is an effect of speeding up the process.

"If the adopter wasn't prepared for that, it can have a detrimental impact on the placement."

IN NUMBERS

28.7 weeks - average length of family court proceedings completed*

67% - proportion of family court regions that had average case times of more than 26 weeks (28 out of 42 regions)*

7,426 - number of children involved in public law applications*

*Figures for October and December 2014

Source: Ministry of Justice